I used to dread seeing the white screen of doom. The Server Error (500) page that meant my whole Django site had gone down. One small mistake could make everything disappear, and that feeling of panic never really left me.

But with the latest Django version (5.2 as I write this), I have noticed that things are a little different. When something goes wrong now, Django seems to fail more gracefully. Instead of the entire site collapsing, only the affected page breaks. It is such a relief to see that Django can isolate problems rather than take everything with it.

When My 404 Page Broke (and Why That’s a Good Thing)

Recently, I created a custom 404 page that shows a list of recent blog posts. It worked perfectly until I accidentally broke it. When I typed in a fake URL to test the 404 page, I expected my lovely custom design. Instead, I got the standard 500 error page.

That told me something was wrong with my 404 template, not the site itself. The rest of the website carried on working. No crash. No panic.

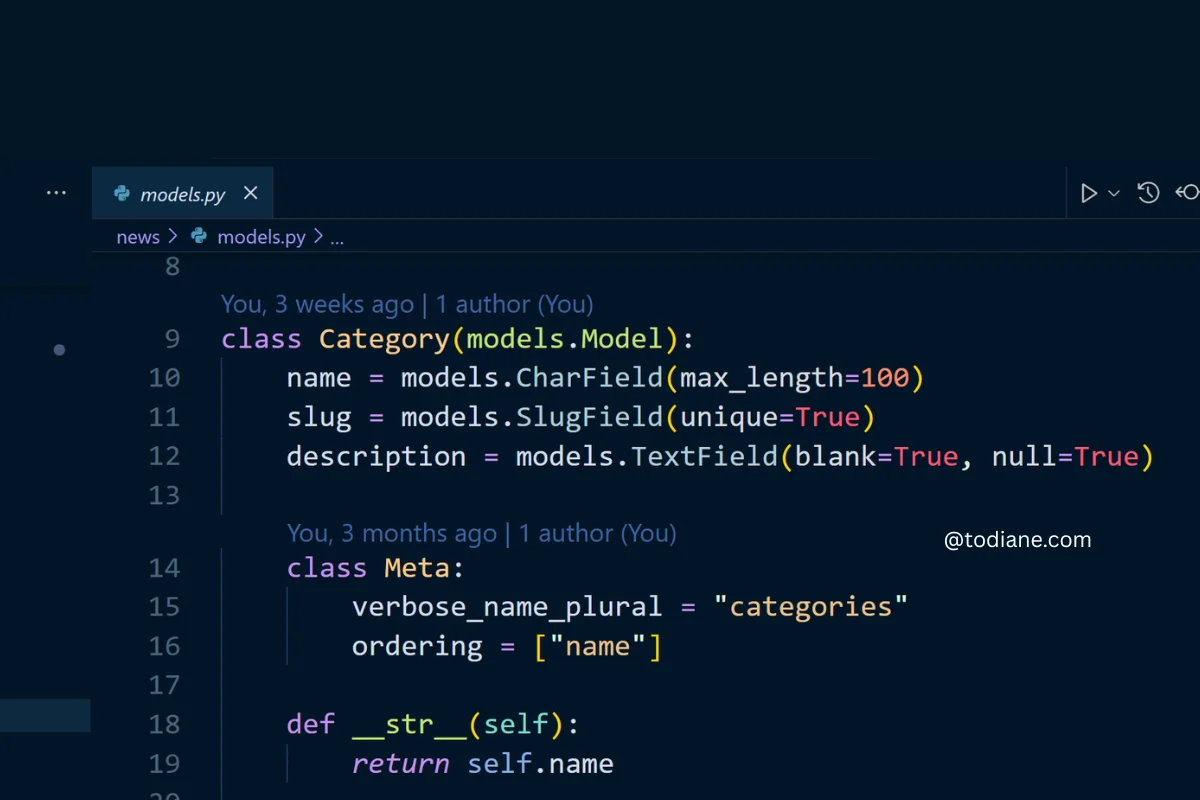

After checking the template, I realised I had duplicate lines — {% extends "base.html" %} and {% block content %} appearing twice. A small mistake, easily fixed. The fact that Django contained the error and kept the rest of the site running made me appreciate just how much better error handling has become.

How Django Handles Errors Now

For anyone new to Django, the DEBUG setting controls how much detail Django shows when something fails.

When DEBUG = True, Django displays detailed error pages in your browser. You get the traceback, line numbers, and helpful hints.

When DEBUG = False, those details are hidden from public view for security reasons, and Django serves your custom 404, 403, or 500 templates instead.

On my local setup, I often switch between the two. When something breaks, I temporarily turn DEBUG = True, fix the problem, test it again, then immediately turn it back off.

It might sound simple, but it gives me confidence. I can dig into what’s wrong, fix it safely, and know that when DEBUG = False, Django won’t expose any sensitive information to the public.

Setting Up Email Notifications for Errors

One of the best decisions I made was setting up email notifications for Django errors. If an error occurs when DEBUG = False, I receive an email almost instantly. It includes the error type, the request path, and even the traceback.

Here’s the key part of how it works in settings.py:

ADMINS = [('Your Name', 'you@example.com')]

EMAIL_BACKEND = 'django.core.mail.backends.smtp.EmailBackend'

SERVER_EMAIL = 'server@example.com'

Whenever Django encounters an unhandled exception, it emails the site admins automatically. It’s a small setup step that saves so much time, especially when you are managing your own VPS.

My tip: use a separate email address just for these messages, so they do not get lost among everyday emails.

Moving Beyond print() — Using Logging Properly

When I first started learning Django, I used print() for everything. I would sprinkle print() statements through my views, trying to see what was happening. It worked for a while, but once I moved to production, I realised print() doesn’t go anywhere useful and it can even slow things down.

Now, I rely on Django’s built-in logging system. It’s much cleaner and more powerful.

Here’s a simple version of my setup:

LOGGING = {

'version': 1,

'disable_existing_loggers': False,

'handlers': {

'file': {

'level': 'ERROR',

'class': 'logging.FileHandler',

'filename': '/var/log/django/error.log',

},

},

'loggers': {

'django': {

'handlers': ['file'],

'level': 'ERROR',

'propagate': True,

},

},

'filters': {

'require_debug_false': {

'()': 'django.utils.log.RequireDebugFalse',

},

},

}

This setup saves errors to a log file on my VPS, and only when DEBUG = False. That filter is important - it keeps my local development logs tidy but records production issues.

Inside my code, I can now use:

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

try:

# risky code here

except Exception:

logger.exception("Something went wrong in the custom 404 page")

That single line - logger.exception() - gives me the full traceback in the logs without exposing anything to the public.

How I Investigate Errors on My VPS

Here is exactly how I handle errors step by step when I suspect something’s wrong:

Get the alert. If Django emails me, I check the subject line first. It usually tells me which view or template caused the issue.

SSH into the VPS. I open my terminal and connect to the server. Then I navigate to my project directory.

View recent logs. I run: tail -f /var/log/django/error.log

This shows the latest entries in real time. If I need to look for something specific, I use: grep "Traceback" /var/log/django/error.log

Check web server logs. If the Django log looks clean but the site still fails, I check Nginx or Gunicorn logs: tail -f /var/log/nginx/error.log

Switch DEBUG = True temporarily. When I cannot reproduce the issue locally and sometimes just because it is quick to do! I turn on debug mode briefly to see the full traceback, fix the error, then switch it straight back off.

Review templates. Most of my errors happen in templates, especially custom ones like my 404 page. I look for: Missing {% endblock %} (although that error would show up locally but sometimes I send to production without checking - naughty I know!)

Duplicated {% extends %}. Variables that don’t exist in the context. Test the page again. I reload the same URL and make sure the correct page loads.

Archive old logs. I like to clear or rotate logs once I’m done so that new errors stand out clearly.

Keeping a Calm Workflow

I have more learning to do before I would call myself a Django expert, but the process no longer feels stressful. With logging, email alerts, and the ability to toggle debug mode safely, I can handle errors without panic.

My small checklist before deploying now includes:

- Logging set up correctly

- Email notifications working

- 404 and 500 pages tested intentionally

It feels like a partnership - Django does its best to contain problems, and I do my part by setting up systems to spot them early.

Reflections

I no longer fear the 500 error page.

When something breaks, I take it as feedback, not failure.

Django’s newer versions handle errors more gracefully, and with logging and email alerts, I can quietly fix things without losing control of the whole site.

I am not an expert developer, but I am learning to stay calm, read the clues, and trust Django’s tools to guide me. That alone has changed how I feel about debugging - from dread to curiosity.

Thanks for sharing: